With this pretty recognisable title, Cui Jian [崔健] (born 1961) achieved his lifelong status as the "Father of the Chinese Rock'n Roll". It is not an exaggeration to state that Cui Jian's influence over the youth culture in China has been historical (spanning some good 50 years as of now), and his signature theme 一无所有 [Nothing to my name], a banner song of the Tiananmen protest movement, has granted him virtual immortality among much of the Chinese community on all its locations, from the mainland to special designated areas such as Hong Kong (where he first got published), to Taiwan, and even to the overseas Chinese diaspora. The gifted young musician had only released a previous album before this one, a cassette recording discretely being shared on the Chinese mainland before being re-released, again, in Hong Kong; he had been playing for some 5 years before, his first band [七合板] dating from 1984.

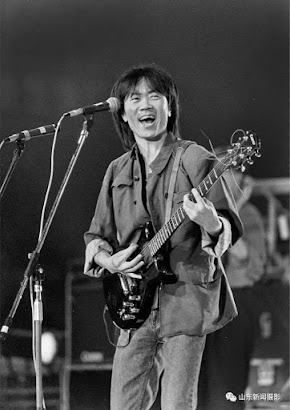

Some of the most recognisable features of Cui Jian's incredible musical style are prominently biographical. Its hard to ignore the high-pitched, almost battlecry sounding suona [嗩吶] vibrating all through this whole record, along with flutes and saxophones of various kinds. In fact this instrument was played by his father, of Korean ascendence, and Cui Jian started learning it by age 14; his interest in traditional music would never wane, even when he got interested in rock during his twenties by listening to smuggled tapes coming from Southeast Asia. He himself learned playing guitar during this period and, being a Beijing youngster at the start of the eighties, his life naturally merged into the historical events which were going to take place. Many of the basics in rock music were at the time either unknown or seldom used in Chinese bands, with most 'pop-ish' formations being influenced by trends in Thailand, Singapore or Vietnam, notably those of traditional or even conservative fashion. Cui Jian's love of highly distorted guitars, crushing drums and showy live performances were of course disliked by party authorities in mainland China, highly suspicious of any "westernization trends", acting in the same fashion of that of the USRR. His initial mimicking the bands he had been listening to on smuggled or stranded cassettes was therefore a concern on itself, but in Jian's case it only got compounded by the unavoidable presence of politics on the way.

However, and despite western perceptions of China in the eighties, the country was not a monolithic monster. Sure, China was no country for rock'n roll, as Jian laments on all his interviews, but it was undergoing a deep transformation. The Cultural Revolution had ended in -parcial if not total- failure in 1976, and thus the Communist Party of China had diversified itself considerably. Within its highest ranks were hardliners from Mao's time, free-market sympathisers, nationalists, institutional reformers, technocrats and pro-westernization voices. Thus, despite Cui Jian being "unsavory" to old ears, he was not thrown in a jail, nor ever fined; same happened with the thousand of students joining the angry protests in favor of expanding the negative freedoms (in a philosophical definition) within the Chinese political system, such as freedom of the press and concerning artistic endeavors. A more pressing kernel of dissatisfaction was the CPC's turning its back on regular workers on its pursue of a more "liberalized" economy -meaning increasing the production demands without offering anything on exchange-, and therefore the Tiananmen movement was also a workers endeavor.

The CPC allowed occupation of the quite important Tiananmen square until constant failure of the negotiations led to the pressed resignation of the progressive, liberal minded wing of the party, and thus the hardliners adquired full control over the situation. The best reference for understanding the whole debacle -aside from books- is still no doubt The Gate of Heavenly Peace [天安门] (1995), where Cui Jian's music also features. His participation on Tiananmen was, nevertheless, not very political, and more of a byproduct of the youth leadership organizing the sittings. Jian's wisely crafted lyrics are notorious for being quite ambiguous: on one hand, many are simply love songs; on the other, their lyrics pursue deeper themes of disenfranchisement and alienation, or operate as methapors for themes not allowed by the political authorities. This is particularly the case with two of his most "polemic" songs of this period -and, I might add, some of his best ones- such as 一无所有 [Nothing to my name] and 一块红布 [A Piece Of Red Cloth], which got him notoriety at the time as he performed with a red cloth covering his eyes. However, Cui Jian did not see himself as radical or revolutionary at the time, but rather as a vehicle for the discomfort among the young people of the country, and a means for reflection in the effort of making China a more free, diverse country; he stated: "Music doesn't need to have political messages, but rather political questions".

The CPC allowed occupation of the quite important Tiananmen square until constant failure of the negotiations led to the pressed resignation of the progressive, liberal minded wing of the party, and thus the hardliners adquired full control over the situation. The best reference for understanding the whole debacle -aside from books- is still no doubt The Gate of Heavenly Peace [天安门] (1995), where Cui Jian's music also features. His participation on Tiananmen was, nevertheless, not very political, and more of a byproduct of the youth leadership organizing the sittings. Jian's wisely crafted lyrics are notorious for being quite ambiguous: on one hand, many are simply love songs; on the other, their lyrics pursue deeper themes of disenfranchisement and alienation, or operate as methapors for themes not allowed by the political authorities. This is particularly the case with two of his most "polemic" songs of this period -and, I might add, some of his best ones- such as 一无所有 [Nothing to my name] and 一块红布 [A Piece Of Red Cloth], which got him notoriety at the time as he performed with a red cloth covering his eyes. However, Cui Jian did not see himself as radical or revolutionary at the time, but rather as a vehicle for the discomfort among the young people of the country, and a means for reflection in the effort of making China a more free, diverse country; he stated: "Music doesn't need to have political messages, but rather political questions".After the Tiananment events faded, Cui Jian was unoficially blacklisted by the Chinese government, being unable to organize tours during the nineties; however, he was allowed to play in small venues, and to communicate with his audience from mouth to mouth. In a quite CPC-ish way of dealing with off-limit topics, Cui Jian was allowed to being himself without causing much noise, even if standing on a kind of uncomfortable position (the same way China bans foreign websites but allows VPN services to be freely available, or bans religious proselitism while allowing religious practise and attitudes at their designated spaces). However, this situation reached an end during the 2000's, with Jian reaching public notoriety again: TV appearances, new album releases and live tours, and even opening a venue for The Rolling Stones. He has also attempted a few indie movies and documentaries, and keeps playing his songs to this day. Despite the CPC's steel hand over the economy and the political atmosphere of China, its opening the country to global influences is undeniable and a welcoming feature of these last few years (now jeopardised by USA tariffs and the COVID situation). Its TV is as currently filled with celebrities as the American or South Korean ones, private enterprises have a long share of the country's wealth and, via C-Drama and C-Pop, its entertainment and commodity industries are slowly catching up to the country's intrinsic power and economic influence. It thus makes sense to suppose that Cui Jian will be -at least kind of- unchained for a long time to came (even if occasional censorship of dissident musicians happens, Li Zhi [李志] being a recent case).

However, no matter how much money Chinese tycoons spend on their entertainment industry promotion, Cui Jian has something they can't pay for: edge. Not just that of his coarse, powerful and expressive voice, or the raw production of his tracks, but the edge of authenticity, and or survival. China was no country for rock, but Jian made it happen, and even made it big for a time; his years spent on the media shadow made hard for him to make a living, and his distinctive red-starred cap (a symbol most Chinese would recognise on a heatbeat) was seen at any and all places trying to keep the tradition alive. And even today, when scarce punk or metal bands can be spotted in China -none of them really influential at this point-, Jian's songs have the taste and trial of historical times behind them, and their lyrics keep asking veiled questions to anyone willing to listen. Is this feat that sets Cui Jian apart from almost every other modern Chinese musician. On a landscape still hard for the genre to persist or flourish (with idol stars taking over yearly, with the endearing softness most Chinese pop brings with it), his voice is just a necessary as before.

To my mind, this album is still Jian's crowning achievement. Fresh, innovative, beautiful and diverse, I'll be forever thankful it was my first approach to Chinese rock in general (of which there are a lot of hidden gems). Lets review the songs one by one. The opening is 新长征路上的摇滚 [Rock 'N' Roll on the New Long March], giving its title to the album itself; it's a rich anticipation of Jian's unique style. A old-style rock'n rolling guitar (its chords in fact almost rockabilly) provides a steady and lively base for the track, sprinkled by a wonderful air section and a lead saxophone. A groovy and powerful bass delivers quite a performance here, even allowing for ingenious transitions between the chorus parts (including an actual choir) and the verses of the track. The drum also covers its entire range, even purely focusing on both hit-hats and crashes at times. Addictive and energic, it is a pretty good start for the record, and its jazzy saxophone solo at the end is honestly impressive. Thus it comprises at least three diferent genres on a single song.

不再掩饰 [No More Disguises] opens up as a nostalgic and frankly pretty 80's rock ballad. A delicate softly distorted guitar builts a dreamy atmosphere with a couple of chords, leaving the action to Jian's impressive voice. It is no wonder Jian's raspy, deep voice has turned into legend in China, where a confluence of both traditional and commercial factors (including the record industry of East Asia in general) usually favors clean, formal and almost boy-ish male voices and intonations as opposed to Jian's passionate abandonment. Toward the second half of this track, a progressive buildup transforms it into an almost punk theme. It includes pads and keys as a novelty, and also displays an arrestingly beautiful saxophone solo. The whole combination of styles is able to blend perfectly, and this piece may be among the best of this whole album. Next track, 让我睡个好觉 [Let Me Sleep], starts on a diametrically opposite fashion, stricking with a prog-rock guitar riff and the high-pitch, almost desperate cry of the suona. The bass on this song is amazing, and provides the verse's base. The guitar is solid rock and roll, creating a rythmic, recurring short phrase before changing to the first great guitar solo -in a quite 80s fashion indeed. Yet, there is also room for another wind solo, and for some soft pads on the background. Jian's voice is also quite amazing here, and the chorus at the end something to embrace. Next track is 花房姑娘[Greenhouse Girl], also among Jian's most celebrated songs. A classic guitar ballad backed by beautiful, dreamy pads, this is nevertheless a vocal-wind based theme. The guitar work is commendable and works like a charm here, adding to the relaxed song -perhaps the only really calm track of this record. The saxophone is simply wonderful here too. Its ending is genius, the chorus intensifying progressively with help of the bass and the ongoing saxo solo. Good stuff. 假行僧 [Fake Monk] is the next track, opening to a much somber atmosphere. The main addition of this track is its including guqin [古琴] to its repertoire; the traditional instrument -even featuring a solo- gives a whole new flavor to both the voice and the modern instrumentals, this time heavily relying on both bass and key works. Its chorus is interesting and somewhat reminiscent of traditional Chinese music also.

不再掩饰 [No More Disguises] opens up as a nostalgic and frankly pretty 80's rock ballad. A delicate softly distorted guitar builts a dreamy atmosphere with a couple of chords, leaving the action to Jian's impressive voice. It is no wonder Jian's raspy, deep voice has turned into legend in China, where a confluence of both traditional and commercial factors (including the record industry of East Asia in general) usually favors clean, formal and almost boy-ish male voices and intonations as opposed to Jian's passionate abandonment. Toward the second half of this track, a progressive buildup transforms it into an almost punk theme. It includes pads and keys as a novelty, and also displays an arrestingly beautiful saxophone solo. The whole combination of styles is able to blend perfectly, and this piece may be among the best of this whole album. Next track, 让我睡个好觉 [Let Me Sleep], starts on a diametrically opposite fashion, stricking with a prog-rock guitar riff and the high-pitch, almost desperate cry of the suona. The bass on this song is amazing, and provides the verse's base. The guitar is solid rock and roll, creating a rythmic, recurring short phrase before changing to the first great guitar solo -in a quite 80s fashion indeed. Yet, there is also room for another wind solo, and for some soft pads on the background. Jian's voice is also quite amazing here, and the chorus at the end something to embrace. Next track is 花房姑娘[Greenhouse Girl], also among Jian's most celebrated songs. A classic guitar ballad backed by beautiful, dreamy pads, this is nevertheless a vocal-wind based theme. The guitar work is commendable and works like a charm here, adding to the relaxed song -perhaps the only really calm track of this record. The saxophone is simply wonderful here too. Its ending is genius, the chorus intensifying progressively with help of the bass and the ongoing saxo solo. Good stuff. 假行僧 [Fake Monk] is the next track, opening to a much somber atmosphere. The main addition of this track is its including guqin [古琴] to its repertoire; the traditional instrument -even featuring a solo- gives a whole new flavor to both the voice and the modern instrumentals, this time heavily relying on both bass and key works. Its chorus is interesting and somewhat reminiscent of traditional Chinese music also. Let's move on to 从头再来 [Do It All Over Again] and ohh boy; I remember being surprised by it. This is 100% a ska song, at all effects, and an amazing one at that; and dates back to the Chinese eighties which is amazing on itself. Uplifting, playful and featuring almost basque-punk vocals at some points, the track is pretty much guitar and bass on the face, with only a couple of synth bridges. The bass does almost all the significant work, along with the vocals; be also ready for a wind ensemble, as it is customary on both ska and Cui Jian's signature themes. This is hands down a favorite, and a lot of fun to listen to. Next track is 出走 [Stepping Out], reminiscent of the second track in that it is a eighties rock ballad, this time featuring keys. It is a contemplative and beautiful track, and it does not explode all the sudden as its counterpart, favouring a slow building up. Its key elements are, without a doubt both voice and saxophone; this latter features one of the greatest, soulful solos I've ever heard. While it also features electric guitar and full on drums, they are eclipsed by the saxo performance and Jian's impressive voice.

We move on to 一无所有 [Nothing to My Name], Jian's signature track. Clean guitars and pads open space for Jian's delivery of the quite recognisable verses and chorus of the track; a bit later they are reinforced by highly distorted guitars and a powerful bass line. Roughly at the first third of the song, something happens; melody breaks and a torrent of suona sound assaults the listener, with guitars hitting powerful low power chords. The suona bit is fully reminiscent of Old China, and its street musicians playing on the old notation system. After this bit, the tempo keeps upping itself, with almost funk-inspired bass lines and clean guitar riffs. The frantic drum then propels the fantastic guitar solo, best of the album no doubt. The famous lyrics describe the feelings of a poor man of lower extraction being refused by a girl due to his not owning anything (something quite a few Chinese man can relate to, since they are expected to buy the family's house and provide a lot for their partner's family); this seemingly mundane social commentary can nevertheless be interpreted politically in Chinese, and it was during the Tiananmen movement's months. The track is quite fantastic and I'd argue a global rock classic waiting to be rediscovered by "westerners". Finally, last track is 不是我不明白 [It's Not That I Don't Understand]. Way more relaxed and upbeat than the previous song, it almost sounds like the credits of a movie ending up, which is not bad on itself. Even Jian's voice relaxes a bit here, featuring on almost spoken voice as the bass and the guitar go about on a more experimental way. The drum work is complimented by a rythm machine -like those of industrial music-, and is in fact reminiscent of German and Russian techno-rock formations, quite popular during those years. As such, it includes a lot of sampling, and its vocals are fast yet more or less monotone (minus a quite punk recurring chorus). While being a less brilliant mix of genres than the rest of this amazing album, it adds another layer to Jian's fabulous hability to mix musical influences, either native or international, traditional and modern.

Since I wrote a lot I'll end it up here, leaving you with a song not included on this album, but quite representative of Jian's style as well. An openly pacifist song, 最后一枪 [The last shot] details the last thoughts of a soldier, wishing the bullet taking his own life would be the last ever. As many of Jian's clips, it also features some visual symbology such as the bullet hitting an egg -a symbol of things to be born-, and the yuxtaposition of firearms with musical instruments. Apparently the song was written as a protest against the China-Vietnam War of 1979, when China forcibly tried to annex the country's northern border while taking advantage of Vietnam's weak state due to the recent Vietnam War and Pol Pot's offensive from Cambodia. Young Cui Jian, then barely 18, wrote the song as an hymn against violence. I translated the video; enjoy!

Comments

Post a Comment