My heart has always been close to William Blake (1757 – 1827), and this summer I finally faced his so-called ''Prophetic Works'', arguibly his major poetic and literary endeavours despite their obscurity, when compared with many other works such as Songs of Innocence and Experience, or The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell. Also, I got to read them in the beautiful two-volume compilation by Edwin J.Ellis; when these arrived, not only were they from 1906 (!) but they were also untrimmed, meaning I was the first person to ever read them. For a 30€ purchase on a London-based store, I was elated I must say. Prior to these major works, I had read almost everything else, starting from the 14 or 15 years of age. How did a teenager get into XVIII english poetry instead of alcohol, shitty people and honestly bad music is perhaps a story for other day; but Poe, Bierce and Lovecraft were also around me at the time, before a stimulus coming from a quite unexpected context made me search for a volume at my local library. Not having internet nor friends went also a long way. Nevertheless I instantly felt asunder by the vast meaning lurking beneath those absolutely beautiful plate drawings, and the masterful art of the aphorism, so present also in Bierce or Nietzsche.

William Blake has been recognised by some as perhaps the greatest total artist of his era, and by others as Britain's greatest poet. Yet, such a pleasant picture was not the agreed consensus by a long time; in fact, the further you go back in History, the sooner you find how most people felt about Blake within his own historical context. A madman of fiery temper, a skilled yet dirt poor printer, a lunatic rambling abount vast cosmologic enterprises and the destiny of mankind. In opinion of others he was a political and religious heretic: a man against churches, schools, kings, slavery and waged labour. An advocate for direct democracy, equality of sexes and free love. Or, as he has been described, a mortal enemy of slavery of any kind: espiritual slavery, artistic, political, social slavery. A great rebellion of thought filled with his innermost sentimentality, there is nothing quite like Blake's production in recorded history. Sure, Swedemborg or Böhme were also religious dissidents struck by visions, and prolific authors of strange and unsettling manuscripts quite out of their own time. Yet, despite some vast and alluring visions, their writing reveals itself as a kind of ''doctrinal or especulative'' writing, the kind which is also found on their philosopher readers: Schelling, Hegel. It is dry, filled with exposition or demonstration, and also kind of conservative in many respects. Blake, on the other side, presents a fully artistic and imaginative body of work. He uses characters in order to declamate, and therefore he does mythopoeia; Blake is a world designer. Yet, unlike (let's say) Tolkien's, his mythic declamations, journeys and upheavals are not to be taken as self-contained fairy tale. They are expositions of thought or history, and doors to Blake's vision of what reality and the human condition actually are. Also, they integrate the entirety of human experience: sexuality, evil, labour and many other themes deemed as taboo at the time, in poetry and otherwise. Blake was not a lofty writer of poetry as many of the other English authors (such as Yeats, Wordsworth or even Wollstonecraft, who he admired), writting on pen and submitting to their editor. Blake was a manual worker; a printer dealing with a big, clunky machinery, surrounded by the vapors of acid used on his lithography, painting by himself, selling by himself. His only companion: his wife, Catherine Blake, to whom he taught writing and reading, as well as his own job. Perhaps prompted by the toxic vapours, Blake died on 1827, fairly unknown until the late XIX- early XX century.

William Blake has been recognised by some as perhaps the greatest total artist of his era, and by others as Britain's greatest poet. Yet, such a pleasant picture was not the agreed consensus by a long time; in fact, the further you go back in History, the sooner you find how most people felt about Blake within his own historical context. A madman of fiery temper, a skilled yet dirt poor printer, a lunatic rambling abount vast cosmologic enterprises and the destiny of mankind. In opinion of others he was a political and religious heretic: a man against churches, schools, kings, slavery and waged labour. An advocate for direct democracy, equality of sexes and free love. Or, as he has been described, a mortal enemy of slavery of any kind: espiritual slavery, artistic, political, social slavery. A great rebellion of thought filled with his innermost sentimentality, there is nothing quite like Blake's production in recorded history. Sure, Swedemborg or Böhme were also religious dissidents struck by visions, and prolific authors of strange and unsettling manuscripts quite out of their own time. Yet, despite some vast and alluring visions, their writing reveals itself as a kind of ''doctrinal or especulative'' writing, the kind which is also found on their philosopher readers: Schelling, Hegel. It is dry, filled with exposition or demonstration, and also kind of conservative in many respects. Blake, on the other side, presents a fully artistic and imaginative body of work. He uses characters in order to declamate, and therefore he does mythopoeia; Blake is a world designer. Yet, unlike (let's say) Tolkien's, his mythic declamations, journeys and upheavals are not to be taken as self-contained fairy tale. They are expositions of thought or history, and doors to Blake's vision of what reality and the human condition actually are. Also, they integrate the entirety of human experience: sexuality, evil, labour and many other themes deemed as taboo at the time, in poetry and otherwise. Blake was not a lofty writer of poetry as many of the other English authors (such as Yeats, Wordsworth or even Wollstonecraft, who he admired), writting on pen and submitting to their editor. Blake was a manual worker; a printer dealing with a big, clunky machinery, surrounded by the vapors of acid used on his lithography, painting by himself, selling by himself. His only companion: his wife, Catherine Blake, to whom he taught writing and reading, as well as his own job. Perhaps prompted by the toxic vapours, Blake died on 1827, fairly unknown until the late XIX- early XX century.

Blake's major works are not an easy read. First, he takes distance of ideas and precepts by placing them on a panoply of characters; then, such characters do not behave as characters at all: they are principles, ideas, and even places. They swarm, transform, and barely follow any kind of ''plot''; their outerworldy behaviour is actually rather close to painting, and the constant production of poweful, dynamic images and tensions. Everything and every action operates at many, many levels. In this respect, few authors have attempted to do such a thing; perhaps aside from Joyce's Finnegans Wake. Funny considering how Blake also had Irish roots. And they had another common characteristic: they both defy any kind of scholarly description. Blake is sometimes described as a romantic or a symbolic author; yet, this would not even begin to describe him. He resembles ancient poetry and mythology such as Hesiod's Theogony (and, despite Blake's appropiation of some Christian imaginery, he was among the first reading the Upanishads and the Gita, as well as ancient English pagan lore) but the result is strikingly modern: he does not shy of using the first person, his likes or dislikes, his contemporary historic times (the American Revolution, as an example). His non-substantialist philosophy transferred to his works and everything melted its own identity to become part of something else, from big epic confrontations to poignant chants of sorrow, to almost psychedelic literature written in Modern English. His paintings and lithography, fostered by an admiration of both Michelangelo and Dürer also cannot be simply brushed off as ''neoclassic''; they also share a primitivism miraculously turned into dynamis.

''Vala'', aka''The Four Zoas: The torments of Love & Jealousy in The death and Judgment of Albion the Ancient Man'' is, as pointed out by Edwin J.Ellis, arguibly Blake's central and most important work. To understand Vala is to understand Blake's main themes at work; its complexity is baffling, its poetry sublime, everything the culmen of Blake's eternal trademark. In this respect, it vastly surpasses his other major prophetic work, ''Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion''. Blake carefully prepared Jerusalem to be his major message to his contemporaries, and it was fully pusblished (lacking a great reception); in contrast, Vala remained an abandoned manuscript which Blake polished until his very death, was often abandoned during several episodes of what we would nowadays call depression, and was put together by him and his wife. It was not published until 1893, by Yeats and Edwin himself. After reading both, Vala really has the upper hand: it's deeper, more beautiful and poignant, and has a better reading pace than Jerusalem. It is also more balanced between pure lyricism and action, and it comprises his themes of revolution and history, rationalism and the imagination, the relationship between sexes, society and spiritual emancipation. According to most interpretations of the work, all these dynamic tensions resolve themselves in a tale about the fall and redemption of mankind ubicated ''in the auricular nerves of Human Life''; the microcosm of the internal life of the mind, which also mirrors the macrocosm of both nature, or existence, and history.

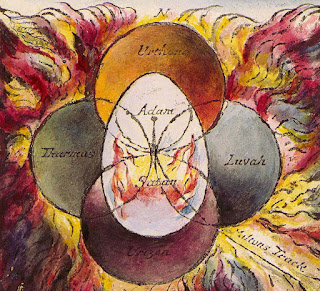

In Vala, Blake presents four ''Zoas'' to us; these are principles or active dynamisms of cosmic reaching. Urthona is the Imagination at the North, Tharmas is Sensation at the West, Luvah is Emotion at the East and Urizen Intellect at the South. I'm simplifying as crazy: there are up to 7 associations with each and every Zoa along the book, including things such as elements of nature, parts of the body, aspects of God, actions, aspects of physis such as space and time, and the list continues. These are not univocal nor unidirectional, and in fact merge constantly as a result of the mixing, opposing or flat out annihilation of ''the Four''. Now, these four, who can in fact assimilate infinite forms by themselves, adopt a variety of them along the story, including the human form of course; these ''deities'' or ideas have female counterparts of themselves, and represent a division at the heart of the principle itself. These are called Emanations, and, while this obviously is a Greek them, they are pretty close to the Vedic idea of Shakti, actually. As Vala is a late work in Blake's life, the influence of his readings of early Orientalist transcripts cannot be overstated. These counterparts spring in various ways, and are deeply connected to Vala's progression, as an upheaval and revolt by Urizen in the South tries to seize Luvah's dominion at the East and have his ratio (as Urizen's Reason) unchecked, governing the North of human existence. What does this ratio, also called Spectre by Blake, consist of?

In Vala, Blake presents four ''Zoas'' to us; these are principles or active dynamisms of cosmic reaching. Urthona is the Imagination at the North, Tharmas is Sensation at the West, Luvah is Emotion at the East and Urizen Intellect at the South. I'm simplifying as crazy: there are up to 7 associations with each and every Zoa along the book, including things such as elements of nature, parts of the body, aspects of God, actions, aspects of physis such as space and time, and the list continues. These are not univocal nor unidirectional, and in fact merge constantly as a result of the mixing, opposing or flat out annihilation of ''the Four''. Now, these four, who can in fact assimilate infinite forms by themselves, adopt a variety of them along the story, including the human form of course; these ''deities'' or ideas have female counterparts of themselves, and represent a division at the heart of the principle itself. These are called Emanations, and, while this obviously is a Greek them, they are pretty close to the Vedic idea of Shakti, actually. As Vala is a late work in Blake's life, the influence of his readings of early Orientalist transcripts cannot be overstated. These counterparts spring in various ways, and are deeply connected to Vala's progression, as an upheaval and revolt by Urizen in the South tries to seize Luvah's dominion at the East and have his ratio (as Urizen's Reason) unchecked, governing the North of human existence. What does this ratio, also called Spectre by Blake, consist of?

The Spectre is the Reasoning Power in Man, and when separated from Imagination and closing itself as in steel in a Ratio of Things of Memory, It thence frames Laws and Moralities

The ratio is characterized by self-defensive rationalization of the kind humans use to merely survive in the natural world at first (that is, a necessary and measured role in life), but that soon after seizes all his instincts and powers, all the days of his life, and all his endeavours in existence. It gives birth to, on one hand, morality (which tries to impose a order on individuals, as represented by States, Churches or human relationships), despised by Blake, and a scientific, materialist approach to nature and the human faculties, which deprives them of their own richness and individuality to become mere useful formality. Blake saw the influx of modern reductionism as the reason behind not only slavery but also industrialization (better captured in his poem ''London''), imposing itself over nature and spontaneous life. And, on the human level, manifested on the stifling, rushed, shallow nature of the human from whom all life has been seized by the process of so called ''civilization'', the ratio.

Once Urizen presides human life, the other Zoas unbalance and enter into a kind of fallen state: Urthona in the North becomes Los, Luvah in the East becomes Orc, and Tharmas in the West his own Spectre. These versions of each Zoa spring their female Emanations: Enitharmon (from Urthona/Los) in the North, Enion (from Tharmas) in the West, Vala (from Luvah) in the East, and Ahania (from Urizen) in the South. United, separated, and reunited from eternity to eternity, these couples are actually the same being, and their disarray during the plot of Vala comes after a period of joyful unity, as most exemplified by Tharmas and Enion as children versions of themselves. These are quite touching I must say. Now, consider everything up to this point a complete and in fact very difficult simplification to make. None of it comes chronologically presented, nor profusely explained; as an example, the figure of Orc has various origins through the work, as both Los and Enitharmon do. Also, every Zoa in any form springs many other Emanations, also refered as ''children'', named or not; Edwin J.Ellis notes how Blake used to think of various mental states as leading to others, and the imagination of dreams, as an example, as a ''child'' to lived experience. Many of them transform into others: they also are like humans, like deities, like ideas, like places.

While all of these ''characters'' have an important role to play, both creative or destructive, during the nine ''Nights'' in which the work is divided, perhaps the couple between Los and Enitharmon is the most interesting one. Some scholars argue that they (to some extent) were projections of both Blake and Catherine themselves, and this would be quite interesting. Depicted as a young, fiery couple with a trickster demeanor and a work to do, both set in motion many events in the chain of this story, all of them ambivalent in nature. It is Enitmaron who calls upon Urizen at the beginning but also the one who disrupts his Emanation Ahania, by leading her into the terrible, distorted existence of Enion (who becomes a metaphor for the pain of existence and madness since the start of Vala) and letting her listen to her wail. Los is the one who puts Orc in chains in fear of being killed by him, but also the one who builts the city of Golgonooza to put an end to Urizen's reach.

And perhaps the greatest undercurrent event during these ''Nights'' is the confrontation between both Orc (a demonlike creature born by Enitharmon, and fused to a rock it was chained to), a spirit of rebellion which perhaps constitutes Urthona's last resort, and Urizen, trying to undo the terrible consequence of his own deed, which depopulates the four realms of the Zoas and also ultimately leads to the Apocalypse, a major confrontation spanning the XVIII and XIX Nights, resolved by a reorganization of them inside Albion (representative of both Mankind and England) which leads to a feast and an end to the slavery of mankind and the division between the sexes. Northrop Frye states that ''There is nothing like the colossal explosion of creative power in the Ninth Night of The Four Zoas anywhere else in English poetry''. The brief summary here exposed simply does not make justice to Blake's tremendous and confounding enterprise, as vast as it could be in the literature of any era. Yet Vala, as expected from a Blakean piece, aside from lacking the theme of ''good versus evil'' (but rather speaking of structural disorder, further rectified and then again rampant), can't be considered a linear story with a kind of happy end. Blake reminds us how the orderly Zoas are not a perfect engineered machinery but rather an equilibrium difficult to navigate, to reconcile: that is why they are filled with ambiguity, why no linear narrative is adequate to descrive their movements or essence. They behave as life itself does: by appearing and dissapearing, by merging, by repeating itself. That is why after all the wonderful images of the XIX Night, when all the mill workers suddenly look up the sky, the walls crumble and they smile after 30 years of not doing so, when the tormented african slave wakes up on his own land, surrounded by his family before the arrival of the slave traders, when the long horrifying forms of Tharmas and Enion become shy children again, still Blake depicts Urthona doing his natural thing:

They build the ovens of Urthona. Nature in darkness groans,

And Men are bound to sullen contemplation all the night,

Restless they turn on beds of sorrow, in their inmost brain

Feeling the crushing wheels: they rise, they write the bitter words

Of stern Philosophy, and knead the bread of Knowledge with tears and groans.

Such are the works of dark Urthona

But Blake had paved the way for this along all his previous works. As he wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: ''Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human Existence''. While his idea of a Divine Vision through Imagination led him to search for the infinite in various aspects of ordinary existence, Blake was not that much of a naive idealist, and his constant use of the ''coincidentia oppositorum'' was a mean of stressing at every level the perfect integration that suffering (or ''evil'' for that matter) has with every aspect of mere existence, and cannot be destroyed without wishing death and complete annihilation. Thus, as Blake himself states, the idea of an everlasting peaceful Eternity is misguided and fallen. To integrate this in amor fati or succumb to death and madness, in this way William Blake paves the way for the Nietzschean and Freudian enterprises, more than one century earlier.

Comments

Post a Comment