This is a book on many things. Mikiso Hane unfolds here an extremelly well-rounded and researched account of Japan's industrialization process and its effects on the traditionally marginal populations, from peasants to outcaste people or burakumin [部落民], female textile workers and girls sold into prostitution. This also includes lots of hard data concerning famine periods, prevalence of land ownership and the multiple historical variants such as army conscription, resource alocation and prevalence of peasant riots. Covering from Meiji restoration to early Shōwa periods, it also includes a background research into late Tokugawa and its social maladies, which prompted the country into modernization at least in the material domain. This is also an overlooked history on the vast human prize behind an Industral Revolution; for, if most people are at least vaguely aware of the child labor and unsanitary conditions, paired with killer labour periods which prevailed in England and EEUU, and many more are fast to point out the brutal human cost of the industrialization process in the Soviet Union or China, the Japanese rise to industrial maturity has come to be regarded as 'fast and miraculous', if not modelic, in most classic scholarship works.

The jump from a feudal caste-enforcing system to industrial, goods-based capitalism was, as widely known, a long and risky one. But there was a vast lot of 'traditional values' driving out the process: just as the English Industrial Revolution and the birth of modern capitalism can't be adressed without dealing with the vast sums of invested money previously adquired via colonialism and slave trade (particularly in Wales), and EEUU's 'free labour' at the hands of slaves. Of course, in both cases and many others, the State's sponsorship of wealthy 'entrepeneurs' such as these, as well as its intervention in squashing any and all revoluts from farmers or industrial workers in the name of 'national comercial interests' was fundamental; also in Japan. In EEUU this even reached the extremes of banning migrants from various countries out of the workforce, the Chinese being an example. In Japan this had to do to the condition of semi-slavery in which the peasantry, traditionally squeezed by the Tokugawa leadership, remained through much of the modern era (and, can be argued, until the very end of WWII). Mikiso Hane not only points out the many economic and educational restraints imposed on them (and they are a lot) but the destitute and miserable existence they underwent both under the feudal period and the modern. The life expectancy was 42 years at the best, the infant mortality rate was abysmal and, both under the old samurai and the new capitalist landlords, they were robbed of half of their earnings. Subsistence under these conditions involved a fight for suvival most of the year; in winter, and in famine periods, most of northern Japan went down on its knees. Hane's statistics of infanticide, cannibalism and child trade are fairly impressive, considering the popular image of Japanese cleanliness and repugnance towards filth (a theme I will adress later).

The jump from a feudal caste-enforcing system to industrial, goods-based capitalism was, as widely known, a long and risky one. But there was a vast lot of 'traditional values' driving out the process: just as the English Industrial Revolution and the birth of modern capitalism can't be adressed without dealing with the vast sums of invested money previously adquired via colonialism and slave trade (particularly in Wales), and EEUU's 'free labour' at the hands of slaves. Of course, in both cases and many others, the State's sponsorship of wealthy 'entrepeneurs' such as these, as well as its intervention in squashing any and all revoluts from farmers or industrial workers in the name of 'national comercial interests' was fundamental; also in Japan. In EEUU this even reached the extremes of banning migrants from various countries out of the workforce, the Chinese being an example. In Japan this had to do to the condition of semi-slavery in which the peasantry, traditionally squeezed by the Tokugawa leadership, remained through much of the modern era (and, can be argued, until the very end of WWII). Mikiso Hane not only points out the many economic and educational restraints imposed on them (and they are a lot) but the destitute and miserable existence they underwent both under the feudal period and the modern. The life expectancy was 42 years at the best, the infant mortality rate was abysmal and, both under the old samurai and the new capitalist landlords, they were robbed of half of their earnings. Subsistence under these conditions involved a fight for suvival most of the year; in winter, and in famine periods, most of northern Japan went down on its knees. Hane's statistics of infanticide, cannibalism and child trade are fairly impressive, considering the popular image of Japanese cleanliness and repugnance towards filth (a theme I will adress later).

Not a single yen was really alocated to help their misery; even when Meiji leaders invested millions of yen in the army or the concrete buildings for the thriving capital cities, doctors and teachers in the countryside often went unpaid. Lack of educational support (in fact, compulsory education only added the burden of having less hands at the farm, and they were forced to pay the entry fee) caused wide abstinence from school among the children, especially girls. Indoctrined into submission and self-sacrifice back from the feudal period, when samurai (often imagined as honorable subjects) had the very right of slaying them off pretty much for fun and peasants were banned from riding on animals, having to recline in their presence, the new 'modern' imperial educational system only aimed of indoctrining them into 'good morals'. Birth control methods were banned by the Meiji government, very keen on 'increasing the work and army force' of the nation despite the rampant poverty of the countryside. Cholera, typhoid or smallpox were rampant, ocassionally arising from easily preventable behaviours. The ministry of Education had very much in mind not teaching the peasants not a single idea that 'which perturb them'; in practise, that meant aggressively fighting any trace of political liberalism from reaching the countryside. Its program's greatest achievement was to, in the course of a single generation, convert thousands of impoverished farmer children into fanatical soldiers acclaiming the Emperor, who was virtually unknown among their elders, accostumed to fear only the local daimyō and its shōgun. Moreover, under feudal Japan peasants were able to collect wood and other natural resources of their province, but under capitalist resource management, they had to pay fees (and very high at that) to the government. The new value of money, now representative of the capital of an entire nation, with a focus on trade and not agriculture, caused the value of rice and many other exchange products from the peasantry to virtually dissapear. These are some of the origins of pretty terrible and dismal situations in modern Japan.

The peasant's terrible plight and their contrast with urban dwellers drives much of Mikiso's research. For, as the peasantry suffered, they looked for other sources of income, from raising silkworms at home in order to sell cocoons to silk factories to virtually selling their daughters into factories and brothels, from the age of 9 onwards. While the government had to put on a façade of civilization not recognizing the previously -and in fact ongoing- human trade culture, its allowing exploitative contracts where minors of age could be bounded by a contract of 6 years in exchange for an 'advance payment' of their salary (often the actual half of that sum), and shipped off far from their parents was indeed not very far from slavery itself. Abuse on these girls, from around 10 to 25 years of age, most of them without any schooling and bounded by a staggering debt which eventually grew for any reason, was sure to ensue. Concerning the industrial sector, most girls were 'send' to silk factories; the silk business was a growing one in modern Japan. Around 40% of Japan's exportations was due to fabric products, and a flourishing amount of factories set out near Lake Suwa. Mikiso Hane provides not only writings and memoirs of the girls workers themselves, but official data from historical sources: the working conditions were no doubt nightmarish. Locked up in their dormitories to prevent them from running away, dozens of women shoven in diminute rooms shared bedding and barely ate in work turns that, in especially abusive cases, reached 5AM. After they finished their turn in the factory hall, damp with the hot water in which chemical components were dissolving (which originated a new epidemic of incurable tuberculosis, when these girls returned home among Japanese not immunized to the disease), they were forced to clean the whole place. Their

The peasant's terrible plight and their contrast with urban dwellers drives much of Mikiso's research. For, as the peasantry suffered, they looked for other sources of income, from raising silkworms at home in order to sell cocoons to silk factories to virtually selling their daughters into factories and brothels, from the age of 9 onwards. While the government had to put on a façade of civilization not recognizing the previously -and in fact ongoing- human trade culture, its allowing exploitative contracts where minors of age could be bounded by a contract of 6 years in exchange for an 'advance payment' of their salary (often the actual half of that sum), and shipped off far from their parents was indeed not very far from slavery itself. Abuse on these girls, from around 10 to 25 years of age, most of them without any schooling and bounded by a staggering debt which eventually grew for any reason, was sure to ensue. Concerning the industrial sector, most girls were 'send' to silk factories; the silk business was a growing one in modern Japan. Around 40% of Japan's exportations was due to fabric products, and a flourishing amount of factories set out near Lake Suwa. Mikiso Hane provides not only writings and memoirs of the girls workers themselves, but official data from historical sources: the working conditions were no doubt nightmarish. Locked up in their dormitories to prevent them from running away, dozens of women shoven in diminute rooms shared bedding and barely ate in work turns that, in especially abusive cases, reached 5AM. After they finished their turn in the factory hall, damp with the hot water in which chemical components were dissolving (which originated a new epidemic of incurable tuberculosis, when these girls returned home among Japanese not immunized to the disease), they were forced to clean the whole place. Their

scarce correspondence -most could not read nor write- was censored. The 'entrepeneurs' of the place were brutal in their squeezing of the workforce. Minor errors in entire lines of productions could cost them the entire salary of the day, if not an actual beating. Only terminal patients of various illnesses were given the leave, and in fact expulsed from the factory without previous notice. Consider also this report compilated by Mikiso Hane:

Slackening the work pace or inattentiveness on the job often resulted in severe punishment by the foremen. A former textile-plant worker reported one such story of a girl who was punished for having fallen asleep on the job. As punishment, the foreman made the girl hold up bales of cotton while standing at attention. He then left for his resting period and didn't return for some time. When the foreman returned, he saw that the girl had been unable to hold up the bales properly, as he ordered, and slapped her. The girl was staggered by this and dropped the bales on the floor, one of which hit the foreman's foot. He lost his temper and gave her a shove. The girl fell upon the teeth of the spinning wheels and was ground to death. The company reported her death as an accident caused by her carelessness. It was commonplace for foremen to slap girl workers, and any foreman or supervisor who was too kind-hearted to punish the girls was seen as being unfit for the job

The steady increase in the number of workers commiting suicide in Lake Suwa led one early Taishō scholar to say sarcastically that the lake was getting shallow because the water was being drained away by the bloated bodies of the suicide victims. The government, before passing a very weak legislation known as the Factory Act, actively crushed any attempt of forming labour unions to fight the inhumane conditions. Exploited by their bosses as men were, the plight of the silk female workers was far worse, and their misery lasted the longer. This, at one level, was due to the perceived lesser value of women in prewar Japan. Not only they often were among the first victims of infanticide during famine, but the rigid family system in Japan placed most of the burdens on female shoulders. As an example, the bride was adopted in her husband's household and there she was virtually condemned to a life of slavery without any compensation, until her husband's mother died and she took over the management of the family. It was not unusual to marry young girls to much older men, even to arrange marriages between uncles and nieces. Many girls also commited suicide because of that. They were expected to be docile, and not undergo any kind of education. And of course, in times of famine and when textile work was unavailable, many were sold into brothels.

The prostitution business in Japan, already set by the Edo period, only grew during industrialization. In fact, it itself became almost a national industry, sponsored by institutions such as the local owners themselves but also the growing army and the government. The vast majority of traffic involved of course girls from poor and destitute rural communities. While the geisha [芸者] inhabiting the famous red district of Kyoto and other places often led miserable lifes and were regularly mistreaten, they along with the oiran [花魁] constituted the cusp of the pyramid of brothel trade; millions of women were on the bottom. As it was the case in tea houses, girls were often sold at the age of 6 or 9 years onward, to funge as kamuro [禿] or downright child servants, at the service of particular geisha or the owner himself. While they were not supposet to 'take clients' -prostitute themselves- until age of 13, their life as unpaid servant -again, sold under a debt contracted by the 'advance payment' of her family- was pretty bleak also. Most faced their plight until the end of their lifes: once sold into prostitution, the heavy social condemnation reduced them to actual outcastes, in most cases excluding them from any other kind of ocupation whatsoever. Most males did not see them as actual human beings, in fact. The fact that many of them were sold without any part on it (in fact, a lot of these children and their families were willfully deceived by the broker) did not cross the mind of both owners and clients, who only saw them as greedy young girls, who should even be punished; their beatings and murder at the hands of dealers was barely prosecuted by the government. Moreover, Japanese expansionism in Asia carried the custom with it, and girls trafficked out of Japan, or Karayuki-san (唐行きさん) faced the worst of destinies, most of them ever unable to return and completely at the will of their owners and the locals, whose language they completely ignored. But perhaps the most insidious aspect of brother trafficking was its hypocrisy, and its justification by better-off people.

The prostitution business in Japan, already set by the Edo period, only grew during industrialization. In fact, it itself became almost a national industry, sponsored by institutions such as the local owners themselves but also the growing army and the government. The vast majority of traffic involved of course girls from poor and destitute rural communities. While the geisha [芸者] inhabiting the famous red district of Kyoto and other places often led miserable lifes and were regularly mistreaten, they along with the oiran [花魁] constituted the cusp of the pyramid of brothel trade; millions of women were on the bottom. As it was the case in tea houses, girls were often sold at the age of 6 or 9 years onward, to funge as kamuro [禿] or downright child servants, at the service of particular geisha or the owner himself. While they were not supposet to 'take clients' -prostitute themselves- until age of 13, their life as unpaid servant -again, sold under a debt contracted by the 'advance payment' of her family- was pretty bleak also. Most faced their plight until the end of their lifes: once sold into prostitution, the heavy social condemnation reduced them to actual outcastes, in most cases excluding them from any other kind of ocupation whatsoever. Most males did not see them as actual human beings, in fact. The fact that many of them were sold without any part on it (in fact, a lot of these children and their families were willfully deceived by the broker) did not cross the mind of both owners and clients, who only saw them as greedy young girls, who should even be punished; their beatings and murder at the hands of dealers was barely prosecuted by the government. Moreover, Japanese expansionism in Asia carried the custom with it, and girls trafficked out of Japan, or Karayuki-san (唐行きさん) faced the worst of destinies, most of them ever unable to return and completely at the will of their owners and the locals, whose language they completely ignored. But perhaps the most insidious aspect of brother trafficking was its hypocrisy, and its justification by better-off people.

The jump from a feudal caste-enforcing system to industrial, goods-based capitalism was, as widely known, a long and risky one. But there was a vast lot of 'traditional values' driving out the process: just as the English Industrial Revolution and the birth of modern capitalism can't be adressed without dealing with the vast sums of invested money previously adquired via colonialism and slave trade (particularly in Wales), and EEUU's 'free labour' at the hands of slaves. Of course, in both cases and many others, the State's sponsorship of wealthy 'entrepeneurs' such as these, as well as its intervention in squashing any and all revoluts from farmers or industrial workers in the name of 'national comercial interests' was fundamental; also in Japan. In EEUU this even reached the extremes of banning migrants from various countries out of the workforce, the Chinese being an example. In Japan this had to do to the condition of semi-slavery in which the peasantry, traditionally squeezed by the Tokugawa leadership, remained through much of the modern era (and, can be argued, until the very end of WWII). Mikiso Hane not only points out the many economic and educational restraints imposed on them (and they are a lot) but the destitute and miserable existence they underwent both under the feudal period and the modern. The life expectancy was 42 years at the best, the infant mortality rate was abysmal and, both under the old samurai and the new capitalist landlords, they were robbed of half of their earnings. Subsistence under these conditions involved a fight for suvival most of the year; in winter, and in famine periods, most of northern Japan went down on its knees. Hane's statistics of infanticide, cannibalism and child trade are fairly impressive, considering the popular image of Japanese cleanliness and repugnance towards filth (a theme I will adress later).

The jump from a feudal caste-enforcing system to industrial, goods-based capitalism was, as widely known, a long and risky one. But there was a vast lot of 'traditional values' driving out the process: just as the English Industrial Revolution and the birth of modern capitalism can't be adressed without dealing with the vast sums of invested money previously adquired via colonialism and slave trade (particularly in Wales), and EEUU's 'free labour' at the hands of slaves. Of course, in both cases and many others, the State's sponsorship of wealthy 'entrepeneurs' such as these, as well as its intervention in squashing any and all revoluts from farmers or industrial workers in the name of 'national comercial interests' was fundamental; also in Japan. In EEUU this even reached the extremes of banning migrants from various countries out of the workforce, the Chinese being an example. In Japan this had to do to the condition of semi-slavery in which the peasantry, traditionally squeezed by the Tokugawa leadership, remained through much of the modern era (and, can be argued, until the very end of WWII). Mikiso Hane not only points out the many economic and educational restraints imposed on them (and they are a lot) but the destitute and miserable existence they underwent both under the feudal period and the modern. The life expectancy was 42 years at the best, the infant mortality rate was abysmal and, both under the old samurai and the new capitalist landlords, they were robbed of half of their earnings. Subsistence under these conditions involved a fight for suvival most of the year; in winter, and in famine periods, most of northern Japan went down on its knees. Hane's statistics of infanticide, cannibalism and child trade are fairly impressive, considering the popular image of Japanese cleanliness and repugnance towards filth (a theme I will adress later).Not a single yen was really alocated to help their misery; even when Meiji leaders invested millions of yen in the army or the concrete buildings for the thriving capital cities, doctors and teachers in the countryside often went unpaid. Lack of educational support (in fact, compulsory education only added the burden of having less hands at the farm, and they were forced to pay the entry fee) caused wide abstinence from school among the children, especially girls. Indoctrined into submission and self-sacrifice back from the feudal period, when samurai (often imagined as honorable subjects) had the very right of slaying them off pretty much for fun and peasants were banned from riding on animals, having to recline in their presence, the new 'modern' imperial educational system only aimed of indoctrining them into 'good morals'. Birth control methods were banned by the Meiji government, very keen on 'increasing the work and army force' of the nation despite the rampant poverty of the countryside. Cholera, typhoid or smallpox were rampant, ocassionally arising from easily preventable behaviours. The ministry of Education had very much in mind not teaching the peasants not a single idea that 'which perturb them'; in practise, that meant aggressively fighting any trace of political liberalism from reaching the countryside. Its program's greatest achievement was to, in the course of a single generation, convert thousands of impoverished farmer children into fanatical soldiers acclaiming the Emperor, who was virtually unknown among their elders, accostumed to fear only the local daimyō and its shōgun. Moreover, under feudal Japan peasants were able to collect wood and other natural resources of their province, but under capitalist resource management, they had to pay fees (and very high at that) to the government. The new value of money, now representative of the capital of an entire nation, with a focus on trade and not agriculture, caused the value of rice and many other exchange products from the peasantry to virtually dissapear. These are some of the origins of pretty terrible and dismal situations in modern Japan.

The peasant's terrible plight and their contrast with urban dwellers drives much of Mikiso's research. For, as the peasantry suffered, they looked for other sources of income, from raising silkworms at home in order to sell cocoons to silk factories to virtually selling their daughters into factories and brothels, from the age of 9 onwards. While the government had to put on a façade of civilization not recognizing the previously -and in fact ongoing- human trade culture, its allowing exploitative contracts where minors of age could be bounded by a contract of 6 years in exchange for an 'advance payment' of their salary (often the actual half of that sum), and shipped off far from their parents was indeed not very far from slavery itself. Abuse on these girls, from around 10 to 25 years of age, most of them without any schooling and bounded by a staggering debt which eventually grew for any reason, was sure to ensue. Concerning the industrial sector, most girls were 'send' to silk factories; the silk business was a growing one in modern Japan. Around 40% of Japan's exportations was due to fabric products, and a flourishing amount of factories set out near Lake Suwa. Mikiso Hane provides not only writings and memoirs of the girls workers themselves, but official data from historical sources: the working conditions were no doubt nightmarish. Locked up in their dormitories to prevent them from running away, dozens of women shoven in diminute rooms shared bedding and barely ate in work turns that, in especially abusive cases, reached 5AM. After they finished their turn in the factory hall, damp with the hot water in which chemical components were dissolving (which originated a new epidemic of incurable tuberculosis, when these girls returned home among Japanese not immunized to the disease), they were forced to clean the whole place. Their

The peasant's terrible plight and their contrast with urban dwellers drives much of Mikiso's research. For, as the peasantry suffered, they looked for other sources of income, from raising silkworms at home in order to sell cocoons to silk factories to virtually selling their daughters into factories and brothels, from the age of 9 onwards. While the government had to put on a façade of civilization not recognizing the previously -and in fact ongoing- human trade culture, its allowing exploitative contracts where minors of age could be bounded by a contract of 6 years in exchange for an 'advance payment' of their salary (often the actual half of that sum), and shipped off far from their parents was indeed not very far from slavery itself. Abuse on these girls, from around 10 to 25 years of age, most of them without any schooling and bounded by a staggering debt which eventually grew for any reason, was sure to ensue. Concerning the industrial sector, most girls were 'send' to silk factories; the silk business was a growing one in modern Japan. Around 40% of Japan's exportations was due to fabric products, and a flourishing amount of factories set out near Lake Suwa. Mikiso Hane provides not only writings and memoirs of the girls workers themselves, but official data from historical sources: the working conditions were no doubt nightmarish. Locked up in their dormitories to prevent them from running away, dozens of women shoven in diminute rooms shared bedding and barely ate in work turns that, in especially abusive cases, reached 5AM. After they finished their turn in the factory hall, damp with the hot water in which chemical components were dissolving (which originated a new epidemic of incurable tuberculosis, when these girls returned home among Japanese not immunized to the disease), they were forced to clean the whole place. Theirscarce correspondence -most could not read nor write- was censored. The 'entrepeneurs' of the place were brutal in their squeezing of the workforce. Minor errors in entire lines of productions could cost them the entire salary of the day, if not an actual beating. Only terminal patients of various illnesses were given the leave, and in fact expulsed from the factory without previous notice. Consider also this report compilated by Mikiso Hane:

Slackening the work pace or inattentiveness on the job often resulted in severe punishment by the foremen. A former textile-plant worker reported one such story of a girl who was punished for having fallen asleep on the job. As punishment, the foreman made the girl hold up bales of cotton while standing at attention. He then left for his resting period and didn't return for some time. When the foreman returned, he saw that the girl had been unable to hold up the bales properly, as he ordered, and slapped her. The girl was staggered by this and dropped the bales on the floor, one of which hit the foreman's foot. He lost his temper and gave her a shove. The girl fell upon the teeth of the spinning wheels and was ground to death. The company reported her death as an accident caused by her carelessness. It was commonplace for foremen to slap girl workers, and any foreman or supervisor who was too kind-hearted to punish the girls was seen as being unfit for the job

The steady increase in the number of workers commiting suicide in Lake Suwa led one early Taishō scholar to say sarcastically that the lake was getting shallow because the water was being drained away by the bloated bodies of the suicide victims. The government, before passing a very weak legislation known as the Factory Act, actively crushed any attempt of forming labour unions to fight the inhumane conditions. Exploited by their bosses as men were, the plight of the silk female workers was far worse, and their misery lasted the longer. This, at one level, was due to the perceived lesser value of women in prewar Japan. Not only they often were among the first victims of infanticide during famine, but the rigid family system in Japan placed most of the burdens on female shoulders. As an example, the bride was adopted in her husband's household and there she was virtually condemned to a life of slavery without any compensation, until her husband's mother died and she took over the management of the family. It was not unusual to marry young girls to much older men, even to arrange marriages between uncles and nieces. Many girls also commited suicide because of that. They were expected to be docile, and not undergo any kind of education. And of course, in times of famine and when textile work was unavailable, many were sold into brothels.

The prostitution business in Japan, already set by the Edo period, only grew during industrialization. In fact, it itself became almost a national industry, sponsored by institutions such as the local owners themselves but also the growing army and the government. The vast majority of traffic involved of course girls from poor and destitute rural communities. While the geisha [芸者] inhabiting the famous red district of Kyoto and other places often led miserable lifes and were regularly mistreaten, they along with the oiran [花魁] constituted the cusp of the pyramid of brothel trade; millions of women were on the bottom. As it was the case in tea houses, girls were often sold at the age of 6 or 9 years onward, to funge as kamuro [禿] or downright child servants, at the service of particular geisha or the owner himself. While they were not supposet to 'take clients' -prostitute themselves- until age of 13, their life as unpaid servant -again, sold under a debt contracted by the 'advance payment' of her family- was pretty bleak also. Most faced their plight until the end of their lifes: once sold into prostitution, the heavy social condemnation reduced them to actual outcastes, in most cases excluding them from any other kind of ocupation whatsoever. Most males did not see them as actual human beings, in fact. The fact that many of them were sold without any part on it (in fact, a lot of these children and their families were willfully deceived by the broker) did not cross the mind of both owners and clients, who only saw them as greedy young girls, who should even be punished; their beatings and murder at the hands of dealers was barely prosecuted by the government. Moreover, Japanese expansionism in Asia carried the custom with it, and girls trafficked out of Japan, or Karayuki-san (唐行きさん) faced the worst of destinies, most of them ever unable to return and completely at the will of their owners and the locals, whose language they completely ignored. But perhaps the most insidious aspect of brother trafficking was its hypocrisy, and its justification by better-off people.

The prostitution business in Japan, already set by the Edo period, only grew during industrialization. In fact, it itself became almost a national industry, sponsored by institutions such as the local owners themselves but also the growing army and the government. The vast majority of traffic involved of course girls from poor and destitute rural communities. While the geisha [芸者] inhabiting the famous red district of Kyoto and other places often led miserable lifes and were regularly mistreaten, they along with the oiran [花魁] constituted the cusp of the pyramid of brothel trade; millions of women were on the bottom. As it was the case in tea houses, girls were often sold at the age of 6 or 9 years onward, to funge as kamuro [禿] or downright child servants, at the service of particular geisha or the owner himself. While they were not supposet to 'take clients' -prostitute themselves- until age of 13, their life as unpaid servant -again, sold under a debt contracted by the 'advance payment' of her family- was pretty bleak also. Most faced their plight until the end of their lifes: once sold into prostitution, the heavy social condemnation reduced them to actual outcastes, in most cases excluding them from any other kind of ocupation whatsoever. Most males did not see them as actual human beings, in fact. The fact that many of them were sold without any part on it (in fact, a lot of these children and their families were willfully deceived by the broker) did not cross the mind of both owners and clients, who only saw them as greedy young girls, who should even be punished; their beatings and murder at the hands of dealers was barely prosecuted by the government. Moreover, Japanese expansionism in Asia carried the custom with it, and girls trafficked out of Japan, or Karayuki-san (唐行きさん) faced the worst of destinies, most of them ever unable to return and completely at the will of their owners and the locals, whose language they completely ignored. But perhaps the most insidious aspect of brother trafficking was its hypocrisy, and its justification by better-off people.

To justify this practise, the society played up the sacrifice of the daughters as an exemplary manifestation of filial piety. The ethos of the society conditioned the girls into believing that it was their duty as daughters to become prostitutes to aid their families. National political leaders did nothing to change this situation.

Of course, this conveniently virtuous argument was useful to disuade clients, 'merchants', and mainly army officials of the goodness of the status-quo. Only quite small organizations such as the Salvation Army or familiars of these girls (and many conscripted low-rank soldiers did share origins with them) protested at all the brothel system. And of course, the least convinced by such words were the girls themselves. Mikiso Hane brings many testimonies such as this one:

I must make known to the public that we are living like animals with only the veneer of human beings. In reality we are cut off from the world of humanity. We would like to ask out fellow women to think seriously about the reality of a Japan where such a system of public brothels is recognized and protected by law (...) We who are weak and frail are deprived of all our rights and are forced to sell our flesh and make indescribable sacrifices. How do you think the owners treat us? They are like bloodsuckers who drive many of us to death (...) When will the day come when people like me, who are engaged in such a shameful profession, dissapear from the world? I wish to escape from this miserable, shameful abyss as soon as possible and join the community of normal human beings.

But if girls sold into brothels became outcastes at all effects, there was another group in Japan which were in fact born with such an estigma. This book is among the few who delves deep into the plight of these people, still known as burakumin [部落民]. During the Tokugawa period they were the scrap of the social ladder, and were forced to remain as such. Names they received were eta (穢多) ['pile of filth'] or hinin (非人) ['not human']. Despite debate among modern scholars, some of them claiming they were originally from Korea or perhaps former tribespeople such as the Ainu, the actual general consensus is that the outcastes or 'riverbed people', who are completely Japanese both in ancestry and custom, were discriminated against for having 'unclean', 'impure' ocupations, in the shintō religious system. In other words, they dealt with either butchery and the killing of animals for leather or meat, or with human or horse corpses, and a long etc. It appears to be the case that in early Japanese history people who lived in 'impure surroundings' (near graveyards, crematoriums, etc.) or dealt with blood could receive purification at shrines, and improve their status by taking another profession. But under Tokugawa rule, hereditary castes were fixed, with the samurai at the head of the scheme. By doing this, the Bakufu caused the descendants of these people to suffer their status, even if their changed professions. Ingraded beliefs regarding pollution transformed them and their families into the universal scapegoats, in a brutal fashion which only worsened with time. Under Tokugawa law, those who broke ordenances -and lived- were also brought down to eta status.

But if girls sold into brothels became outcastes at all effects, there was another group in Japan which were in fact born with such an estigma. This book is among the few who delves deep into the plight of these people, still known as burakumin [部落民]. During the Tokugawa period they were the scrap of the social ladder, and were forced to remain as such. Names they received were eta (穢多) ['pile of filth'] or hinin (非人) ['not human']. Despite debate among modern scholars, some of them claiming they were originally from Korea or perhaps former tribespeople such as the Ainu, the actual general consensus is that the outcastes or 'riverbed people', who are completely Japanese both in ancestry and custom, were discriminated against for having 'unclean', 'impure' ocupations, in the shintō religious system. In other words, they dealt with either butchery and the killing of animals for leather or meat, or with human or horse corpses, and a long etc. It appears to be the case that in early Japanese history people who lived in 'impure surroundings' (near graveyards, crematoriums, etc.) or dealt with blood could receive purification at shrines, and improve their status by taking another profession. But under Tokugawa rule, hereditary castes were fixed, with the samurai at the head of the scheme. By doing this, the Bakufu caused the descendants of these people to suffer their status, even if their changed professions. Ingraded beliefs regarding pollution transformed them and their families into the universal scapegoats, in a brutal fashion which only worsened with time. Under Tokugawa law, those who broke ordenances -and lived- were also brought down to eta status.

Nonetheless, just as the rulers allowed the samurai to abuse the commoners, they permitted the commoners to abuse the burakumin. All sorts of restrictive measures were imposed on the eta-hinin. They were restricted in where they could live, quality of housing, mobility in and out their hamlets, clothing, hairdo, and even footwear. One burakumin, reflecting on the plight of his ancestors, remarked: ''They were not treated as human beings. They were not allowed to wear any footwear but had to go about barefoot. They could use only straw ropes as belts, and only straws to their hair. They were forbidden to leave their hamlet from sunset to sunrise. They were not allowed to associate with other people. When it was necessary to see others, for some business reason, they had to get on their hands and knees before they could speak''. When the burakumin encountered people above them in the social hierarchy, they had to get out of their way or get on their hands and knees until the others passed by. In some areas they were required to wear special identification marks, such as a yellow collar. They were banned from the shrines and temples of non-eta communities, and intermarriage with other classes was strictly forbidden

If these accounts seem really feudal, that situation did not really improve after the Meiji restoration and the early XX century, when the cast system was abolished and the government issued order of allowing burakumin in public spaces and treat them as citizens. Sad as it sounds, these dispositions actually raised peasant urprisings, demanding the government to overturn the burakumin liberation. For generations they were instructed to despise and mistreat them, and a mere change in legality did not affect cultural customs. The burakumin's social plight could be compared with that of jews and especially gipsies in European history but just as the Japanese feudal system was actually harsher on the peasants than its european counterpart, the mistreatment of burakumin was also open and proudly bigoted. An account describes how a burakumin was beaten to death by a mob in a shintō shrine, in Asakusa (a district of the capital). The authorities replied to his family that the life of an eta was 1/7 the life of a normal person, so until seven eta were killed they could not arrest one Japanese. Date: 1859.

Their life was so stunted by restriction and misery that it barely improved under the Meiji system. Compulsory schooling, which few managed to access, meant for them terrible experiences at the hands of classmates, or low rank-employers. Both men and women were subjected to wretched experiences, many of which Mikiso also portrays via personal testimones, diaries and witnesses. Only during the American ocuppation did their situation really improve, and yet discrimination among them has persisted, with companies purguing them out due to their former status, discovered via family registry (戸籍). As it was the case with the 'virtuous behaviour' regarding the brothel system, the eta were in turn condemned for an activity that many japanese people actually demanded: the consumption of meat was not seen as a polluting act, only the killing of the animal. Therefore, even if many Japanese desired leather products or to eat sukiyaki, there was a eta behind doors, paying the prize of such goods. If did not matter that fishermen were not deemed polluted even if engaged in the same kinf of activity: the burakumin served as an escape valve for the frustration of commoners and empoverished peasants, who adscribed to them 'an odious nature, treachery, and malice'. Japanese religions did not care for them, and they were forbidden at shrines and temples, at the same time that buddhist did preach they were paying an abhorrent karma and thus were born as eta.

Of course, this conveniently virtuous argument was useful to disuade clients, 'merchants', and mainly army officials of the goodness of the status-quo. Only quite small organizations such as the Salvation Army or familiars of these girls (and many conscripted low-rank soldiers did share origins with them) protested at all the brothel system. And of course, the least convinced by such words were the girls themselves. Mikiso Hane brings many testimonies such as this one:

I must make known to the public that we are living like animals with only the veneer of human beings. In reality we are cut off from the world of humanity. We would like to ask out fellow women to think seriously about the reality of a Japan where such a system of public brothels is recognized and protected by law (...) We who are weak and frail are deprived of all our rights and are forced to sell our flesh and make indescribable sacrifices. How do you think the owners treat us? They are like bloodsuckers who drive many of us to death (...) When will the day come when people like me, who are engaged in such a shameful profession, dissapear from the world? I wish to escape from this miserable, shameful abyss as soon as possible and join the community of normal human beings.

But if girls sold into brothels became outcastes at all effects, there was another group in Japan which were in fact born with such an estigma. This book is among the few who delves deep into the plight of these people, still known as burakumin [部落民]. During the Tokugawa period they were the scrap of the social ladder, and were forced to remain as such. Names they received were eta (穢多) ['pile of filth'] or hinin (非人) ['not human']. Despite debate among modern scholars, some of them claiming they were originally from Korea or perhaps former tribespeople such as the Ainu, the actual general consensus is that the outcastes or 'riverbed people', who are completely Japanese both in ancestry and custom, were discriminated against for having 'unclean', 'impure' ocupations, in the shintō religious system. In other words, they dealt with either butchery and the killing of animals for leather or meat, or with human or horse corpses, and a long etc. It appears to be the case that in early Japanese history people who lived in 'impure surroundings' (near graveyards, crematoriums, etc.) or dealt with blood could receive purification at shrines, and improve their status by taking another profession. But under Tokugawa rule, hereditary castes were fixed, with the samurai at the head of the scheme. By doing this, the Bakufu caused the descendants of these people to suffer their status, even if their changed professions. Ingraded beliefs regarding pollution transformed them and their families into the universal scapegoats, in a brutal fashion which only worsened with time. Under Tokugawa law, those who broke ordenances -and lived- were also brought down to eta status.

But if girls sold into brothels became outcastes at all effects, there was another group in Japan which were in fact born with such an estigma. This book is among the few who delves deep into the plight of these people, still known as burakumin [部落民]. During the Tokugawa period they were the scrap of the social ladder, and were forced to remain as such. Names they received were eta (穢多) ['pile of filth'] or hinin (非人) ['not human']. Despite debate among modern scholars, some of them claiming they were originally from Korea or perhaps former tribespeople such as the Ainu, the actual general consensus is that the outcastes or 'riverbed people', who are completely Japanese both in ancestry and custom, were discriminated against for having 'unclean', 'impure' ocupations, in the shintō religious system. In other words, they dealt with either butchery and the killing of animals for leather or meat, or with human or horse corpses, and a long etc. It appears to be the case that in early Japanese history people who lived in 'impure surroundings' (near graveyards, crematoriums, etc.) or dealt with blood could receive purification at shrines, and improve their status by taking another profession. But under Tokugawa rule, hereditary castes were fixed, with the samurai at the head of the scheme. By doing this, the Bakufu caused the descendants of these people to suffer their status, even if their changed professions. Ingraded beliefs regarding pollution transformed them and their families into the universal scapegoats, in a brutal fashion which only worsened with time. Under Tokugawa law, those who broke ordenances -and lived- were also brought down to eta status.Nonetheless, just as the rulers allowed the samurai to abuse the commoners, they permitted the commoners to abuse the burakumin. All sorts of restrictive measures were imposed on the eta-hinin. They were restricted in where they could live, quality of housing, mobility in and out their hamlets, clothing, hairdo, and even footwear. One burakumin, reflecting on the plight of his ancestors, remarked: ''They were not treated as human beings. They were not allowed to wear any footwear but had to go about barefoot. They could use only straw ropes as belts, and only straws to their hair. They were forbidden to leave their hamlet from sunset to sunrise. They were not allowed to associate with other people. When it was necessary to see others, for some business reason, they had to get on their hands and knees before they could speak''. When the burakumin encountered people above them in the social hierarchy, they had to get out of their way or get on their hands and knees until the others passed by. In some areas they were required to wear special identification marks, such as a yellow collar. They were banned from the shrines and temples of non-eta communities, and intermarriage with other classes was strictly forbidden

If these accounts seem really feudal, that situation did not really improve after the Meiji restoration and the early XX century, when the cast system was abolished and the government issued order of allowing burakumin in public spaces and treat them as citizens. Sad as it sounds, these dispositions actually raised peasant urprisings, demanding the government to overturn the burakumin liberation. For generations they were instructed to despise and mistreat them, and a mere change in legality did not affect cultural customs. The burakumin's social plight could be compared with that of jews and especially gipsies in European history but just as the Japanese feudal system was actually harsher on the peasants than its european counterpart, the mistreatment of burakumin was also open and proudly bigoted. An account describes how a burakumin was beaten to death by a mob in a shintō shrine, in Asakusa (a district of the capital). The authorities replied to his family that the life of an eta was 1/7 the life of a normal person, so until seven eta were killed they could not arrest one Japanese. Date: 1859.

Their life was so stunted by restriction and misery that it barely improved under the Meiji system. Compulsory schooling, which few managed to access, meant for them terrible experiences at the hands of classmates, or low rank-employers. Both men and women were subjected to wretched experiences, many of which Mikiso also portrays via personal testimones, diaries and witnesses. Only during the American ocuppation did their situation really improve, and yet discrimination among them has persisted, with companies purguing them out due to their former status, discovered via family registry (戸籍). As it was the case with the 'virtuous behaviour' regarding the brothel system, the eta were in turn condemned for an activity that many japanese people actually demanded: the consumption of meat was not seen as a polluting act, only the killing of the animal. Therefore, even if many Japanese desired leather products or to eat sukiyaki, there was a eta behind doors, paying the prize of such goods. If did not matter that fishermen were not deemed polluted even if engaged in the same kinf of activity: the burakumin served as an escape valve for the frustration of commoners and empoverished peasants, who adscribed to them 'an odious nature, treachery, and malice'. Japanese religions did not care for them, and they were forbidden at shrines and temples, at the same time that buddhist did preach they were paying an abhorrent karma and thus were born as eta.

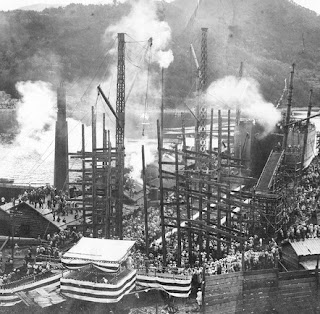

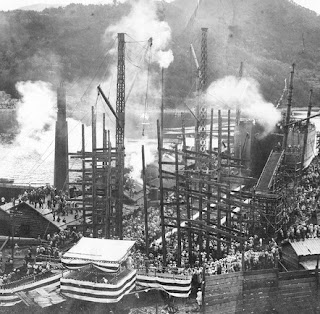

The book also coves multitude of other topics, such as work regulations, the plight of the cotton or the coal worker, the attempts of rebellion on the part of peasants, textile workers or burakumin (such as the Rice Riots of 1918, fairly important to the Japanese socialists at the time) and the building up of the war machine of the Shōwa era. But just going by these examples, the main aim of the work cn be well represented: to what little degree 'modern' Japan was by the European standards of modernity, that is, philosophical enlightment. The divide between the rural and urban was all-too bleeding. While peasants were perceived almost as animals born to work, and filled with superstition and ignorance, they recogniced the well-educated urbanites and merchants as the destinataries of all their strenuous work at the farm, which benefitted those living close to 'development zones', close to the government and its institutions. The main objective of the Meiji government since its foundation had been to 'strengthen the country to keep the barbarians away', and most of the gross product went into building an army. The success of the following militar encounters, such as the first war with China and Russia, persuaded both zaibatsu (財閥) industrialists (now rich due to blatant exploitation) and army officials of being in the 'right path'. This was the main cause of all the suffering inflicted on Japan in prewar years: while a flourishing new elite wore western clothing and discovered the world beyond Japan, as flamant warships crowded the Pacific Ocean, most people remained fairly provincial, and had trouble accesing the most basic necessities of life.

The handsight, with time compulsory education rose, and the lot of both women and outcastes improved from feudal times. While in this period of modernity such advances (and the technological ones) were only accesible to an exclusive elite of families, greatly benefited by the development of a shark capitalism, they later expanded to many others. All along, it was no coincidence that these families, the owners of those factories, and most intelectual figures of the period, were descendants of people with samurai status.

The handsight, with time compulsory education rose, and the lot of both women and outcastes improved from feudal times. While in this period of modernity such advances (and the technological ones) were only accesible to an exclusive elite of families, greatly benefited by the development of a shark capitalism, they later expanded to many others. All along, it was no coincidence that these families, the owners of those factories, and most intelectual figures of the period, were descendants of people with samurai status.

Comments

Post a Comment