高村 光太郎 [Takamura Kōtarō] (1883-1956) was a polifacetic artist, sculptor, poet, and translator. Son of a famous sculptor, he studied the craft in New York, under Gutzon Borglum; there he also discovered Walt Whitman's poetry and he himself began writing free verse. After a while, he then studied for four years in France, reading Verlaine, Baudeleire, Rimbaud and Verhaeren among others, being most impressed by Auguste Rodin (for whom he wrote a biography, and translated many writings). The ideal of a sculptor-poet became his own, singling him out from all Japanese artists of his time. In the years to come, he would also produce Japanese translations of Verhaeren, Romain Rolland, Van Gogh and many more. His first collection of original poems, ''Distance'' was published in 1914, a pivotal year for he also got married to 高村 智恵子 [Takamura Chieko] (1886-1938). This is story is really about her, for Kōtarō's greatest poetic archievement, one of the immortal hights in Japanese modern poetry is 智恵子抄 [Selections of Chieko], a remembrance work of his late wife, the tragically schizophrenic free spirit who shared with him years of material poverty and yearning for beauty. An oil painter herself, Chieko lived a creative hurricane in the intellectual atmosphere of Tokyo during Taishō and Shōwa eras, during which talented artists and intellectualls (many of them female, such as Akiko Yosano or Raichō Hiratsuka) shared both preocupations and adversities; immortal names had trouble getting by, while producing daring poems and essays, forever transforming Japan's cultural landscape. Raichō recalls their first meeting at Tokyo's Japan Women's University, and her contributionn to Japan's first feminist magazine, 青鞜 [Seitō].

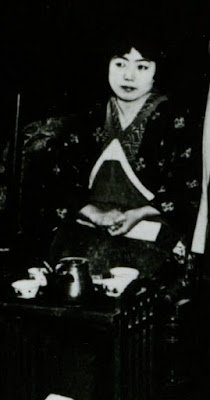

One of my partners was Nagamuna Chieko, who had entered one year after me. She later married Takamura Kōtarō and became widely known through Chieko-shō, the series of poems he wrote about her. She was shy and withdrawn, too timid to look at anyone in the face, her voice barely audible. But she was good at tennis (...) I often wondered where she got her strength. She rarely spoke, and since I was just as taciturn, we played tennis together but never had a sustained conversation. After graduation I had occasionally seen her from a distance (...) In fact, it would have been hard to miss Chieko -the collar of her kimono was daringly pulled back and the hem was trailing, and her loose hair flopped over her forehead. Stranger was her languorous walk, at once demure and seductive. Even as a student she had been eccentric, not at all the typical home economics student. I had watched her with friendly fascination, and in choosing an artist for our cover, I thought of her at once. I also hoped she would join the society. Chieko accepted our request but declined to become a member.

One of my partners was Nagamuna Chieko, who had entered one year after me. She later married Takamura Kōtarō and became widely known through Chieko-shō, the series of poems he wrote about her. She was shy and withdrawn, too timid to look at anyone in the face, her voice barely audible. But she was good at tennis (...) I often wondered where she got her strength. She rarely spoke, and since I was just as taciturn, we played tennis together but never had a sustained conversation. After graduation I had occasionally seen her from a distance (...) In fact, it would have been hard to miss Chieko -the collar of her kimono was daringly pulled back and the hem was trailing, and her loose hair flopped over her forehead. Stranger was her languorous walk, at once demure and seductive. Even as a student she had been eccentric, not at all the typical home economics student. I had watched her with friendly fascination, and in choosing an artist for our cover, I thought of her at once. I also hoped she would join the society. Chieko accepted our request but declined to become a member.

This edition of Chieko's Sky includes not only Kōtarō's poems but also his essay ''The latter half of Chieko's life'' and illustrations of Chieko's handmade papercuts (produced during her last years at the mental hospital). Being these poems the most important feature, it's worth analysing them. As Paul Archer indicates: ''The poems have a restless searching, an elemental flow. Their structure is organic, as far removed as possible from the rigid linguistic and structural forms of traditional verse''. Indeed Kōtarō's work here is free in form and themes, a long way far from tanka or haiku, that propells his poetry to an equal footing with western modern productions. Rather than seeking the approvation of the classical poetry authorities, he belonged to the Pan Club, a group forwarding décadentisme in artwork and lifestyle (abandoning the latter as soon as he married). There is an eerie, beautiful quality to all these compositions, along with the experimental constructions typical of free verse. This version also recreates the exclusively modernist Japanese treatment of kanji by oddly grouping pharagraphs, and omitting capital letters so as to recreate an free-associating endless flow of language. Yet, of course, the Japanese original is really untranslatable.

There are strong opinions about Chieko's downfall from a Cézanne enthusiast to schizophrenia, whether it was developed by external factors or she was born with it. Daughter to a modestly wealthy family of wine sellers, right as she became fascinated with painting her father died, and her family went totally bankrupt; the familiar house in the countryside burnt to the ground. She cried for her family, without ever mentioning the material loss. Caught in Tokyo, a city whithout nature (fundamental to her stability) nor sky, she also suffered from pleuresy and was often bedridden; eccentric and solitary by nature, she felt lonely at those times. Her best oil works were rejected at the first Exhibit she submitted them: that was the first and last time. Not that Chieko ever complained about these things; they just happened, and she endured them in gentle smile and silence. She did not understand money nor the future, and a growing detachement from the world grew unnoticedly in her.

To think of her now, she seemed to have hidden within her a fate that made it impossible for her to survive safely in this world. As I recall, it seemes to me at times that she was a soul only temporarily of this world. She had no wordly greed; her life was sustained solely by love and art. She was always young. In addition to her spiritual youthfulness, her face revealed extraordinary juvescence. Whenever I traveled with her, wherever we'd go, people took her for my sister or daughter (...) At the time of our marriage, I could hardly imagine her in old age and I once asked jokingly, ''Will you ever become an old lady?'' I remember that she answered casually, ''I'll die before I get old''. And so she did.

Years before her death by tuberculosis in 1938, Chieko had attempted suicide in 1932, overdosing on a 25-gr. bottle of sleeping powders. This seems to have been a crucial moment in her mental health; barely breathing and her forehead burning, she was taken to Kudanza Hospital. Her suicide farewell, written on a clean note ''did not betray the slightest mark of brain disorder. After a month's treatment and nursing, she recovered and came home. For a month or so, she was in good health, but then all sorts of mental disorders became noticeable''. Was it related to cerebral damage product of the intoxication? Did it prompt a hidden proclivity of her mind? In any case, why did she attempted suicide? This last question is answered by Kōtarō's memoir:

Though she did not say so, she had despaired of her oil painting. It couldn't have been an easy affair for her to despair of the art she loved so passionately and regarded as her life work. Years later, on the night she attempted suicide by poison, a basket of fruit just bought at Senbikiya Store was found placed like a still life in the adjacent room, and a new canvas was found standing on the easel. My heart was pained at seeing it. I wanted to cry aloud.

Misteriously, as she was recovering that first month, and with doctors hiding her prognosis, she hugged Kōtarō and whispered ''I'll be a wreck''. The progressive spiral into psychologycal detachement was from then on well documented by hospital staff. It also is the painful material that makes up the latter half of Chieko's Sky material, the first comprising their life together, back when Chieko was an eccentric and extraordiary being, yet not touched by the sickness. Sickness that Kōtarō deems that of a soul too pure or self-oblivious for this world, as Chieko indeed became kind of mystical, losing herself in the contemplation of a river, a leaf, the mixture and unexpected depths of colors in any surface, for hours on end.

Misteriously, as she was recovering that first month, and with doctors hiding her prognosis, she hugged Kōtarō and whispered ''I'll be a wreck''. The progressive spiral into psychologycal detachement was from then on well documented by hospital staff. It also is the painful material that makes up the latter half of Chieko's Sky material, the first comprising their life together, back when Chieko was an eccentric and extraordiary being, yet not touched by the sickness. Sickness that Kōtarō deems that of a soul too pure or self-oblivious for this world, as Chieko indeed became kind of mystical, losing herself in the contemplation of a river, a leaf, the mixture and unexpected depths of colors in any surface, for hours on end.

The lemons in the cover of this edition are reminiscent of the last time they conversed before her death, when she played with a fresh one Kōtarō had buy for her and, startled by its strong aroma, she seemed for a single moment to be returning to her senses. In that second, Kōtarō felt compelled to write about that carefree Chieko, slowly passing away, and so he did after years of depression resulting from her death. The result, Chieko's Sky, is not a somber nor sad picture. Everything written here runs smoothly like water, like wind. It's a joyful celebration of life, and of natural and spontaneus life at that (ringing close to Walt Whitman and Transcendentalism in general, so admired by him). It powerfully speaks of love and loss, intimacy and authenticity. As a classic, there are various versions of Chieko's Sky, some of them online. You can check a really good one here; yet this paper version has extra additions as previously discussed. I'll finish with a favourite:

This is how the world is,

A group of nasty callous people

Gripped by the superficial and nothing else.

That's why those who try to be true to themselves

Whether in past times, today, or in the future,

Are judged perversely as not being 'serious'

And suffer the persecution you suffered...

It should be despised, this world,

These little people caught up in its void.

We must do what we have to do,

Follow the road we have to follow,

Respecting who we are...

Comments

Post a Comment